1450-1350 BC

Seal from Ancient Crete

The first image on the right, is the oldest depiction of harness goats which I have been able to find to date. This image was originally carved onto a stone seal (like the one in the 2nd picture), commissioned by a Minoan citizen, in Bronze-age Crete, for stamping wax on important documents. The image shows a beautiful example of a chariot from that era, with a decoratively carved center pole, and a tasseled harness. The team is a very elegant one as well, moving in sync, with their horns and tails held high.

The whereabouts of the original seal, however, are a bit of a mystery. An agate seal featuring a goat drawn chariot, is listed in several catalogs from archeological exhibitions in the early 20th century. Unfortunately, the only image I was able to find of it, was a very low resolution drawing. None of the catalogs I found, had a record of which museum, country, or private collector, owned the seal, or where it went when the exhibitions were over. What records I’ve found, though, stated that the agate seal was discovered in the village of Avdu, near Lyttos, Crete. The seal was estimated to have been crafted by the Minoan civilization, between LM II and IIIA (between 1450 – 1350 BC). That is one old goat cart!

400 BC

Terracotta Jug from Ancient Greece

This Attic oenochoe vessel was made around 400 b.c. It features a young driver, driving a team of energetic bucks, hitched to a small chariot. The goats are wearing bitted bridles, making this the oldest known depiction of goats wearing bits. This jug resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A high resolution image of it can be viewed on the Met Museum website.

200-300 BC

Terracotta Fragment from India

in the vast collection of the Mathura Government Museum, in India, lies a small terracotta fragment. It’s believed to have been made sometime between the 2nd or 3rd century B.C., possibly in the city of Kosambi. However it’s precise location of origin is uncertain. What we do know, is that the fragment depicts a helmeted charioteer, driving what appears to be a three-abreast hitch, beneath a decorated arch; a three-abreast hitch with unmistakable short perky tails, and little laid-back horns.

150 AD

Marble Relief from Ancient Rome

Imagine it’s the 140s in Ancient Rome, and a little boy, named Marcus Cornelius, has just acquired his first goat chariot. It’s a big deal! The goat is a strong one, but little Marcus handles him well, and the two of them become fast friends. Naturally, Marcus Cornelius has to spend time on his studies too, but in his free hours, you can be sure to find him, happily cruising around his sun baked neighborhood, with his sturdy caprine companion, and their handsome little chariot. His parents look on with gentle pride, watching as their son guides his goat with ever increasing skill.

But then, in the year 150, tragedy strikes. Perhaps he fell victim to an incurable illness, or a freak accident; but poor little Marcus Cornelius was no more.

His distraught parents commissioned a marble sarcophagus, and had it carved with their most cherished memories. The mother, nursing her newborn son; the father, holding him, while he plays with a toy; The boy learning lessons with his father; and in the center, Marcus Cornelius, standing with confidence, in his little chariot, urging on his noble harness goat.

The memorial is inscribed: CIL XIV 4875 M(arco) Cornelio M(arci) f(ilio) Pal(atina) Statio P[3] fecer[unt

Or: To Marcus Cornelius Statius, son of Marcus, of the Palatine tribe, p(arents?) made (this sarcophagus).

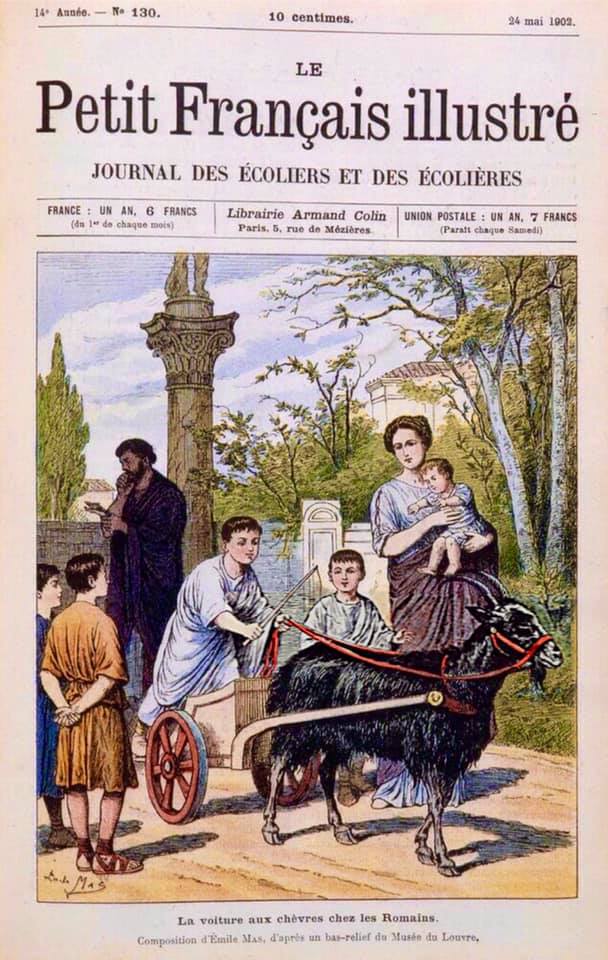

If the purpose of the carved marble relief was to preserve the memory of the young Roman, his family, and his goat cart, they were successful. In 1902, a French youth magazine published an issue featuring an illustration of Marcus Cornelius and his goat chariot on the cover. Simply titled: “The goat cart in Rome” it showed young readers that children in Ancient Rome weren’t so different, and far removed in antiquity, after all! Why, the youngsters of the ancient world had appreciated a good goat cart just as much as they did.

286-312 AD

The Legendary Wei Jie (卫玠), and his Goat Cart

Whether it was Zac Efron, Shaun Cassidy, or Ricky Nelson, It seems every generation of youth has it’s iconic teenage-heartthrob. Jin Dynasty China was no exception. Wei Jie (卫玠) was a scholar who reached legendary status as a teenager, by being both bright, talented, and by all contemporary accounts, fabulously good looking; even being likened to a perfect jade statue, brought to life. And what was the preferred mode of transportation, by this popular young scholar from ancient China? A spiffy little goat cart! When Wei Jie drove out with his goat, he was said to be frequently surrounded, and sometimes completely mobbed by adoring fans and admiriers, making his progress rather slow.

The image of Wei Jie driving his harness goat became cemented in Chinese folklore, and continued to capture the imaginations of artists in the region, for centuries. Both depictions here, are in the Met Museum, and date from the 18th century. The first is a ceramic plate, and the 2nd is an ivory brush holder. The goat on the ivory brush holder wears a sturdy pulling collar; an invention that can be traced back to northern China, during the 3rd century.

1222-1223 AD

The Edda

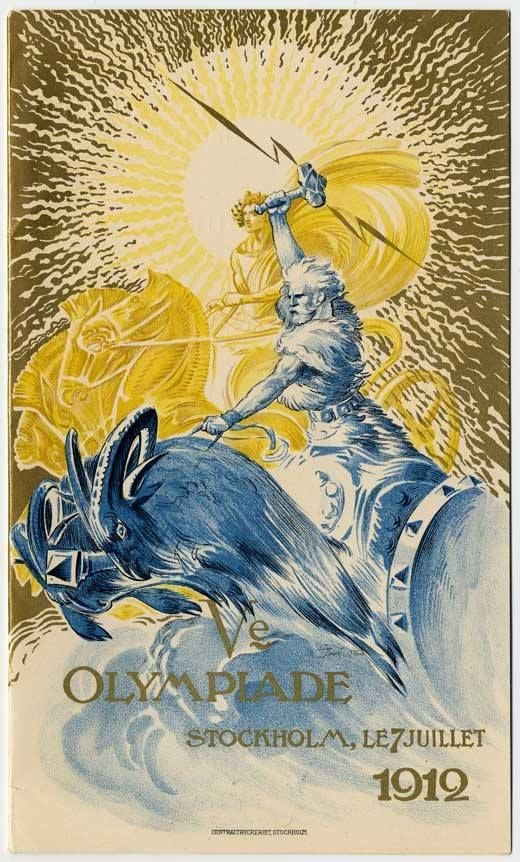

In 13th century Iceland, historian, poet, and public official, Snorri Sturluson, created the great compilation of epic poems and mythology, known today as the Edda.

In it, he transcribed verses, telling of the adventures of Thor: the Norse god of Thunder, lightning, war, and farming; and of his heroic team of harness goats that pulled his chariot, over land, and through the skies. The names of this mythical team are recorded in the Edda, as Tanngnjóstr and Tanngrisnir, which roughly translate to “Gnasher” and “Snarler” respectively. (Possibly referencing goats’ natural propensity to mouthiness).

In the Prose Edda and the Poetic Edda, Thor’s team are depicted as both beautiful, with “splendid horns,” and selflessly heroic; eagerly drawing their chariot on Thor’s quests, running themselves to lameness and exhaustion during battles with giants, and even sacrificing themselves for food, in an emergency, only to be resurrected again with the powers of Thor’s enchanted hammer, Mjolnir.

Today, Thor is most commonly known as the Norse god who wields the powerful hammer Mjolnir, or perhaps as the ancient Norse commander of thunder, and lightning. However, to Snorri, and the poets and scholars before him, Thor’s prowess as a goat charioteer was such, that one of the epithets for Thor, in the Poetic Edda, is “Ruler of Goats.”

Wägner, Wilhelm. 1882. Nordisch-germanische Götter und Helden. Otto Spamer, Leipzig & Berlin. Page 129.